Whooping cough

|

| Whooping cough |

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, is a highly contagious disease that causes classic spasms (paroxysms) of uncontrollable coughing, followed by a sharp, high-pitched intake of air, which creates the characteristic whoop of the disease’s name.

Whooping cough is caused by a bacterium called Bordetella pertussis. B. pertussis causes its most severe symptoms by attaching itself to those cells in the respiratory tract that have cilia.

Cilia are small, hair-like projections that beat continuously, and serve to constantly sweep the respiratory tract clean of such debris as mucus, bacteria, viruses, and dead cells.

When B. pertussis interferes with this normal, janitorial function, mucus and cellular debris accumulate and cause constant irritation to the respiratory tract, triggering coughing and increasing further mucus production.

|

Whooping cough is a disease that exists throughout the world. While persons of any age can contract whooping cough, children under the age of two are at the highest risk for both the disease and for serious complications including death.

Apparently, exposure to B. pertussis bacteria earlier in life gives a person some, but not complete, immunity against infection with it later on. Subsequent infections resemble the common cold.

It is estimated that as many as 120,000 persons in the United States get whooping cough each year. The number of cases has been increasing, with the largest increases found in older children and adults. Between 1993 and 1996, the number of cases increased by 40% in five-to nine-year-old children, 106% in 10–19 year olds, and 93% for persons aged 20 years and older.

Causes and symptoms

Whooping cough has four stages that partially overlap: incubation, catarrhal stage, paroxysmal stage, and convalescent stage.

A person usually acquires B. pertussis by inhaling droplets carrying the bacteria that were coughed into the air by someone already suffering with the infection. Incubation is the symptomless period of seven to 14 days after breathing in the B. pertussis bacteria, and during which the bacteria multiply and penetrate the lining tissues of the entire respiratory tract.

The catarrhal stage is often mistaken for an exceedingly heavy cold. The patient has teary eyes, sneezing, fatigue, poor appetite, and an extremely runny nose (rhinorrhea). This stage lasts about 10–14 days.

The paroxysmal stage, lasting two to four weeks, begins with the development of the characteristic whooping cough. Spasms of uncontrollable coughing, the whooping sound of the sharp inspiration of air, and vomiting are all hallmarks of this stage.

The whoop is believed to occur due to inflammation and mucus that narrow the breathing tubes, causing the patient to struggle to get air into his/her lungs; the effort results in intense exhaustion. The paroxysms (spasms) can be induced by overactivity, feeding, crying, or even overhearing someone else cough.

The mucus that is produced during the paroxysmal stage is thicker and more difficult to clear than the more watery mucus of the catarrhal stage, and the patient becomes increasingly exhausted attempting to clear the respiratory tract through coughing. Severely ill children may have great difficult, maintaining the normal level of oxygen in their systems, and may appear somewhat blue after a paroxysm of coughing, due to the low oxygen content of their blood.

Such children may also suffer from swelling and degeneration of the brain (encephalopathy), which is believed to be caused both by lack of oxygen to the brain during paroxysms, and also by bleeding into the brain caused by increased pressure during coughing. Seizures may result from decreased oxygen to the brain.

Some children have such greatly increased abdominal pressure during coughing that hernias result (hernias are the gila protrusion of a loop of intestine through a weak area of muscle). Another complicating factor during this phase is the development of pneumonia from infection with another bacterial agent, which takes hold due to the patient’s weakened condition.

If the patient survives the paroxysmal stage, recovery occurs gradually during the convalescent stage, usually taking about three to four weeks. However, spasms of coughing may continue to occur over a period of months, especially when a patient contracts a cold, or other respiratory infection.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis based only on the patient’s symptoms is not particularly accurate, as the catarrhal stage may appear to be a heavy cold, a case of the flu, or a simple bronchitis.

Other viruses and tuberculosis infections can cause symptoms similar to those found during the paroxysmal stage. The presence of a pertussis-like cough along with an increase of certain specific white blood cells (lymphocytes) is suggestive of pertussis (whooping cough). However, cough can occur from pertussis-like viruses.

The most accurate method of diagnosis is to culture (grow in the laboratory) the organisms obtained from swabbing mucus out of the nasopharynx (the breathing tube continuous with the nose). B. pertussis can then be identified by examining the culture under a microscope.

Researchers believe that as many as 90% of the cases are not diagnosed, mainly because of the nonspecific symptoms displayed by adults. An adult who has been coughing for months may have whooping cough.

Recent advances in the accuracy of diagnostic tests based on polymerase chain reactions (PCR) are now being applied to whooping cough. Researchers in Seattle are presently working on a PCR-based test for Bordetella pertussis that will improve the speed as well as the accuracy of diagnosing whooping cough.

Treatment

Whooping cough should always be treated with antibiotics and never with only alternative therapies. The following complementary therapies may reduce symptoms and speed recovery. Supportive treatment involves careful monitoring of fluids to prevent dehydration, rest in a quiet, dark room to decrease paroxysms, and suctioning of mucus. Sitting up during coughing attacks may help.

Herbals

The following herbal remedies may help to support antibiotic treatment of whooping cough:

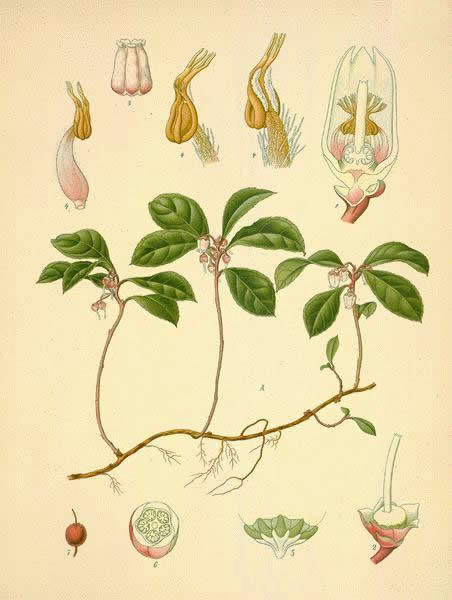

- bryonia (Bryonia alba) tea: spasmodic coughing

- butterbur (Pinguicula vulgaris) infusion: infection and spasms

- evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) oil

- jamaican dogwood (Piscidia erythrina) root or bark: spasms

- lobelia (Lobelia inflata) tea or tincture: spasmodic coughing

- pansy (Viola tricolor) tea or tincture: spasms

- red clover (Trifolium pratense) tea

- santonica (Artemisia cina) powder, tablets, or lozenges

- sea holly (Eryngium planum) infusion: infection and spasms

- skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) powder, extract, or tincture

- sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) infusion: infection and spasms

- thyme (Thymus vulgaris) infusion: infection and spasms

- wild cherry (Prunus serotina) bark infusion or syrup: infection, and spasmodic coughing

Homeopathy

Homeopathic remedies are chosen based upon the family of symptoms displayed by each patient. Remedies for symptom families include:

- Drosera: dry and tickly feeling in throat; violent coughing that induces vomiting; symptoms worse after midnight.

- Kali carbonicum: dry, hard, hacking cough at 3 A.M.; puffy eyelids; exhaustion; chilly feeling.

- Coccus: coughing worse when warm; drinking cold water brings relief; vomiting stringy, transparent mucus.

- Cuprum: coughing spasms cause breathlessness and exhaustion; blue lips; toe and finger cramping; drinking cold water brings relief.

- Kali bichromicum: coughing up yellow, stringy mucus.

- Belladonna: stomach pain before coughing; coughing worse at night; retching with coughing attacks; red face; puffy eyelids.

- Ipecac: sick feeling most of the time; paleness, rigidity, breathlessness, and then relaxation precede vomiting.

Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners use a combination of herbals, acupuncture, and ear acupuncture to treat whooping cough during each stage. Yi Zhi Huang Hua (Herba solidaginis) decoction or a decoction of Bai Mao Gen (Rhizoma imperatae), Lu Gen (Rhizoma phragmitis), and Si Gua Gen (Radix vascularis luffae) may be taken for the early stage of whooping cough. Gasping cough can be treated with a mixture of Wu Gong (Scolopendra) and Gan Cao (Radix glycyrrhizae).

Other remedies

Other remedies may assist in the treatment of whooping cough.

- Dietary supplements include vitamins A and C, beta carotene, acidophilus, lung glandulars, garlic, and zinc.

- Dietary changes include drinking plenty of fluids, eating fruits, vegetables, brown rice, whole grain toast, vegetable broth, and potatoes, and avoiding dairy products.

- Juice therapists recommend orange and lemon juice or carrot and watercress juice.

- Hydrotherapy treatment consists of wet clothes or other material applied to the head or chest to relieve congestion.

- Aromatherapy uses essential oils of tea tree, chamomile, basil, camphor, eucalyptus, lavender, peppermint, or thyme.

- Osteopathic manipulation can reduce cough severity and make the patient feel more comfortable.

Allopathic treatment

Treatment with the antibiotic erythromycin is clearly helpful only in the very early stages of whooping cough, during incubation and early in the catarrhal stage.

In general, however, physicians have used this antibiotic both for treatment of whooping cough itself and to prevent its spread to others in the patient’s community. This type of preventive measure is known as prophylaxis.

Unfortunately, the benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis and treatment for whooping cough are limited because erythromycin-resistant strains of B. pertussis have spread throughout the United States since the first case of erythromycin resistance was identified in Arizona in 1994.

Although erythromycin is still used as of 2003 for both treatment and prophylaxis of whooping cough, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is monitoring the five resistant strains of B. pertussis that have been identified so far.

Expected results

Just under 1% of all cases of whooping cough cause death; in 2000, only two deaths from whooping cough were reported in the United States. Children who die of whooping cough usually have one or more of the following three conditions:

- Severe pneumonia, perhaps with accompanying encephalopathy.

- Extreme weight loss, weakness, and metabolic abnormalities due to persistent vomiting during paroxysms of coughing.

- Other preexisting conditions, so that the patient is already in a relatively weak, vulnerable state (such conditions may include low-birth-weight babies, poor nutrition, infection with the measles virus, presence of other respiratory or gastrointestinal infections or diseases).

Prevention

The mainstay of prevention lies in the immunization program. In the United States, inoculations begin at two months of age. The pertussis vaccine, most often given as one immunization together with diphtheria and tetanus (called DTP), has greatly reduced the incidence of whooping cough. With one shot backed with a 70% immunization rate, two shots increase it to 75–80%, and three to only 85%, it is not a guarantee.

A new formulation of the pertussis vaccine is available. Unlike DTP, which is composed of dead bacterial cells, the newer acellular pertussis vaccine is made up of two to five chemical components of the B. pertussis bacteria. The acellular pertussis vaccine (called DTaP; when combined with diphtheria and tetanus vaccines) greatly reduces the risk of unpleasant reactions, including high fever and discomfort at the injection site.

Because adults are the primary source of infection for children, there has been some talk in the medical community about vaccinating or giving booster vaccinations to adults. A recent increase of pertussis cases among adults in France has led several French medical schools to recommend booster doses of vaccine for adults.